Regular worshipers at Shelter Rock

know that we routinely recite a prayer for our nation as part of our Shabbat

morning service, but I'm not sure that everybody realizes that I myself wrote that prayer as part of the effort to publish Siddur Tzur Yisrael back in

2006. It was a product of its time, too: written just a few years after 9/11, the

sense of America as a nation under siege was audible throughout. (When a

synagogue in Boston years later wrote to ask permission to use my prayer in their

service and specifically asked me for permission to delete the line “May the

wicked plots of whose would destroy us ever come to naught,” I acquiesced,

suggesting—only mostly in jest—that we could compromise by shortening it to

just “May the wicked plotz.” Either they didn’t think that was as funny

as I did or else they didn’t feel the shortened line sufficiently undid what

they clearly considered the line’s untoward bellicosity, but they didn’t go for

it. I decided not to mind and so it entered their worship service as published in

Tzur Yisrael, but without that single line.)

At the time, it felt uncontroversial

to include such a prayer in our prayerbook. Later on, however, I began to get

regular queries about it, some sincere and others merely serving as a means for

the asker to express his or her negative feelings about the president on whom

the prayer invokes God’s blessings. My stock response was (and is) to note wryly

the illogic of not wishing to pray that God grant wisdom and insight to someone

the asker clearly considers in dire need of both, and so the prayer remained (and

remains) part of worship at Shelter Rock.

The idea itself of praying on behalf

of the government and its officials is ancient. Shelter Rockers all know the

words “Pray for the peace of your city for in its peace shall you too have

peace,” but not all know how old they are. And they are very old indeed: the

prophet Jeremiah spoke them in the first decade of the sixth century BCE after

the Babylonians exiled large numbers of ruling-class Judahites in the day of

King Jehoiachin to punish them for their unwillingness to acquiesce to foreign

domination and for their rebelliousness. Nor was this just the prophet’s

personal take on things, but an actual divine oracle. “Thus says the Lord of

hosts, the God of Israel, to all who are carried away captives, to all whom I

have caused to be carried away from Jerusalem to Babylon,” the prophet reports

in God’s name, “‘build houses and dwell in them. Plant gardens and eat their

fruit…Seek the peace of the city to which I have caused you to be carried away as

captives and pray to the Lord for it, for in its peace shall you too have

peace.’” It’s true, I suppose, that the prophet doesn’t specifically tell

the people to pray for the government, but praying for the peace of the city to

which their captors had brought them comes to the same thing: the idea behind

both efforts is to feel justified in praying to God for the city, for the

nation, for its leadership…and all who exercise just and rightful authority in

its governance. This is not presented as mere altruism either, for the prophet

could not be clearer: the people’s security rests in the security of the larger

place in which they live and in the success of its leadership in establishing

that security.

The earliest reference to praying for

the government per se, however, is probably in Pirkei Avot, where we

hear that Rabbi Ḥananiah the Deputy High Priest, liked to tell people to “pray

for the peace of the government, since were it not for the fear of the

government people would swallow each other up alive.” He was in interesting

personality in his own right, Rabbi Ḥananiah, serving as one of the few Temple

officials to seek and attain rabbinic ordination, and thus serving as an

unofficial link between the vanished world of pre-destroyed Jerusalem and the

ongoing work of the rabbinic effort to create a version of Judaism that could

survive the absence of the Temple. And this interesting personality makes an

interesting point: that it behooves law-abiding citizens to pray for their

government officials because it is the latter who are responsible for

maintaining an orderly, peaceful society in which citizens specifically are not

free to cannibalize each other’s work or property.

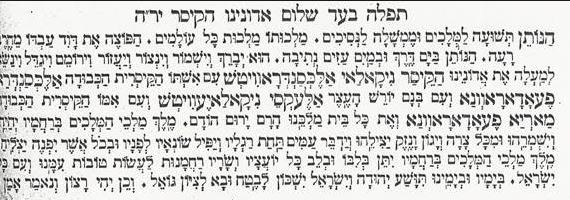

There were many attempts to formulate

prayers for the secular governments of the countries in which Jewish worshipers

lived, but the best known, called Ha-notein Teshu∙ah after its first words, was

in very wide use by the middle of the seventeenth century. (For an interesting

survey by Nathan E. Weisberg of earlier efforts to compose such prayers, click here.) The

great Portuguese/Dutch rabbi, Menasseh ben Israel (1604-1657), for example, cited

it in English translation in a book he wrote to promote the idea that Jews

should be allowed to re-enter and settle in England, declaring it to have be the universal custom of Jews everywhere “on

the Sabbath Day or other solemn feast,” to bless “the Prince of the country

under whom they live, that all Jews may hear it and say, Amen.”

On American soil, the very first

published Jewish prayer published in the New World, called a “form of prayer”

and published by Congregation Shearith Israel in New York in 1760, contained

the Ha-notein Teshu∙ah and specifically called upon congregants to invoke God’s

blessings on “our most gracious Sovereign Lord, King GEORGE the Second, His Royal Highness,

George Prince of Wales, the Princess Dowager of Wales, the Duke, the

Princesses, and all the Royal Family,” and also “the Honourable President, and

the Council of this Province, likewise the Magistrates of New York.” That suited the moment well enough, I

suppose, but by the time the prayer was published for public recitation at the

founding of Congregation Mikveh Israel in Philadelphia in 1782, the royals were

gone and in their place was a reference to “His Excellency the President, and

Honourable Delegates of the United States in Congress Assembled, His Excellency

George Washington, Captain General and Commander of Chief of the Federal Army

of these States.” So we’ve been at this

for a long time, praying for our national leaders sincerely and, I feel sure,

without any sort of ironic overtone.

Over the years, I’ve noticed versions

of the prayer that mention—to cite only nineteenth century personalities—Kaiser

Wilhelm I, Czar Nicholas II, Napoleon, and Queen Victoria. I’m sure there must

be dozens of other examples—I’ve hardly conducted serious research into the

matter and am only mentioning those names I’ve personally come across here and

there in my literary travels. Nor was this a feature solely of Orthodox

worship—by the time the Reform and Conservative movements started publishing

their own prayerbooks, alternate versions of the prayer were routinely composed

and used in place of the older version.

Until the last quarter of the twentieth century, for example, more or

less all Conservative prayerbooks used some version the prayer originally

written by Professor Louis Ginzberg (1873-1953) that asked worshipers to pray

that God “pour out His blessings on this land, on its President, judges,

officers and officials, who work faithfully for the public good.”

We all know

the joke from Fiddler: “Rabbi, may I ask you a question?” “Certainly.” “Is

there are proper blessing for the czar?” “A blessing for the czar? Of course!

May God bless and keep the czar…far away from us!” Hah! But behind the joke is

a piece of reality: prayerbooks from nineteenth and early twentieth century

prayerbooks published in Russia absolutely did include a passage in

which God is asked “to bless,

protect, guard, assist, elevate, exalt, and lift upwards our master Czar

Nikolai Alexandrovich, his wife the honorable Czarina Alexandra Feodorovna,

their son the crown prince Alexi Nikolaiovich, and his mother, the honorable

Czarina Maria Feodoravna. And the entire house of our king, may their glory be

exalted.”

To ask whether we should or shouldn’t pray for the

welfare of our president based on whether we do or don’t approve of his

policies, his politics, or his personal bearing is to miss the point almost

entirely.

We live in an age of extreme uncertainty. Even those

who voted for President Trump are uncertain what specific campaign promises he

will fulfill, or at least attempt to fulfill, and which he will jettison

as undoable or unworkable. (He surely would not be the first president to do that.)

Nor is it clear, even to his most ardent supporters, what the priorities of

this administration are going to be and how vigorously or rigorously those

priorities are going to be pursued. Indeed, by electing a president with no

prior experience in government, our nation has opted for a national leader who

in many ways is himself a tabula rasa, and whose policies and

political stances are clearly still works in progress. Like all Americans, I am

hoping for the best. But when people ask me if I think we should

continue to pray that God bless our President with “wisdom and with a profound

and unyielding devotion to justice, equity, and righteousness,” I can only

answer robustly in the affirmative. Why wouldn’t we pray for something we

all—regardless of our politics and specifically regardless of how we cast our

ballot in November—for something we all fervently want and which our country

unquestionably needs?