March is Women’s History Month, an annual observance since 1987 and one of several such months each year proclaimed as such to encourage the study and appreciation of some specific group within the fabric of American society. Known to most will be Black History Month in February and LGBTQ+ Pride Month in June, but there are also Jewish Heritage Month (May), Hispanic Heritage Month (September 15–October 15), Arab-American Heritage Month (April), German American Heritage Month (October), Italian-American Heritage Month (October), Native American Heritage Month (November), and a few others. (For a full list, click here.) These months mostly come and go, leaving in their wake a few op-ed pieces, some longer essays, perhaps a television special or two. And, of course, they are focused on mostly, although surely not exclusively, by the groups whose heritage they exist to celebrate.

To take note of Women’s History

Month this year, I thought I would write about a woman no one, I’m guessing,

will ever have heard of…and yet who was present at a truly pivotal moment in

Jewish history and who rose remarkably to the occasion.

In general, the role of women in

history has been understudied and underappreciated—which observation applies

across the board to all sorts of academic disciplines. But the degree to which

the prominent Jewish women of antiquity have been mostly forgotten, their names

themselves mostly unknown, is slightly astonishing. And a little depressing too.

Some will have heard of Beruriah, one of the few female Torah scholars from

antiquity to be cited and praised in our literature, but fewer will have heard

of Yalta, an important figure from the mid-3rd century CE, a

communal leader respected and taken fully seriously, and the second-most

mentioned woman in talmudic literature. And fewer still, I think, will have

heard of Imma Shalom, the sister of Rabban Gamliel II of Yavneh and the wife of

Rabbi Eliezer (one of the most prominent sages of his day), who is also quoted prominently

in the Talmud in a way that suggests the respect she commanded in her day and

in her place.

Those three—Beruriah, Yalta, and

Imma Shalom—were part of the rabbinic world. But women also occupied positions

of political importance, some of whom were actually the queens of their

countries. Almost all have been completely forgotten, their very names

unfamiliar despite their prominence in their own day. Queen Helena of Adiabene

is a good example. Adiabene was a small kingdom located in the Kurdish part of

today’s Iraq when Helena and her husband

King Monobaz converted to Judaism early on in the first century CE. Eventually,

Monobaz died and Helena moved to Jerusalem, where she played an important role

as a philanthropist, famously giving gifts of gold to the Temple and personally

dealing with a crippling famine by importing gigantic amounts of food at her

own expense from all over the world to distribute among the hungry. She was

famous for the huge sukkah she constructed in Lod, where she lived

before coming to Jerusalem, and for her even larger tomb which exists to this

day a few miles north of the city. But who has ever heard of her? No one!

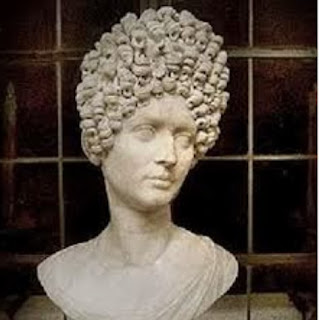

But the personality I thought I’d

write about this week in honor of Women’s History Month is Queen Berenice,

another personality long since forgotten by all. And yet, in her day, she was

the voice of reason that tried—unsuccessfully but nobly—to prevent the destruction

of the Holy City by the Romans…and in the same way Queen Esther saved the Jews

of Persia from annihilation: by getting the Roman most likely to spearhead the

campaign to the destroy the city to fall in love with her and then, at least

possibly, to spare the city simply because she wished him to.

It's a long, complicated story. When

Berenice was still a child, her father was named King of Judea by the Roman

Emperor Caligula. And so, at the age of ten, Berenice became a princess. She

was married at age fourteen to a much older man who died shortly after the

wedding and left her a widow at age sixteen. Her father died shortly after

that, but not before he succeeded in marrying her off a second time, this time

to his own brother, King Herod of Chalcis. (Chalcis was a tiny kingdom in what

today is Lebanon.) And so Berenice became a queen. And that same year she

became a mother too, giving birth to the future king of Chalcis, whom she named

Berenicianus after herself.

When Berenice was twenty, she was

widowed for the second time. For a while, she lived with her brother—who, in

the meantime, had become king of Chalcis and who ruled as Agrippa II—and served

as the female presence in his many palaces across Chalcis and Judea, something

along the lines of how Grover Cleveland’s sister Rose served as First Lady

until he eventually married. And now she really does become a Zelig-like

character, showing up everywhere—including, semi-amazingly, at the trial of

Paul of Tarsus, the founder of the Christianity as we know it and the author of

most of the New Testament.

And then she married for a third

time, choosing yet another king as her husband, a man named Polomon, king of

Cilicia (a small kingdom in today’s Turkey), whom she insisted agree to be

circumcised and fully to convert to Judaism if he wished to have her as his

wife. He did it too! But their union still didn’t last. Why, who knows? Maybe

he resented the whole circumcision thing. Or perhaps they just weren’t meant to

be. But before long she was back in Jerusalem, powerful, famous, and in exactly

the right place to do great good.

The 60s of the first century CE

were a dangerous, difficult time. The Roman governors of Judea, called

procurators, were greedy bullies, or at least most of them were. The procurator

in Jerusalem was a man named Florus, who was eager to steal at least part of

the vast treasury of riches stored in the Temple. When the Jews protested, he

sent in his soldiers to terrify the inhabitants into submission. Berenice,

present in Jerusalem, first sent some of her servants to beg Florus to call off

his goons. And then, when they were rebuffed, she went herself, bare-headed and

barefoot, to beg him to withdraw. In the end, Florus withdrew his men. But Judea

was on the brink of open rebellion against Rome nonetheless. Seeing disaster on

the horizon, Berenice gave a long, passionate speech in which she begged the

locals not to begin a war they could not possibly hope to win. But no one was

in the mood to listen. And so the rebellion began.

Berenice, however, had a plan.

She moved into her brother’s palace at Banias, a lovely and verdant section

even today in Israel, where she was able to hobnob with Roman aristocracy. She

met Vespasian himself, the future emperor who was at the time in charge of

Roman forces in Judea. But it was when she met Vespasian’s son, a young man of

twenty named Titus, that she suddenly saw an “Esther” path forward for herself

and her people. She was in her forties. Titus was just twenty. But he was no

match for her and he fell quickly into her trap. She did her best to keep him

from moving violently against the Jewish rebels, perhaps trying to convince him

that the rebellion would just die out if the Romans didn’t rise to the bait.

Our source for this story is the

work of the Jewish historian Josephus, himself a client of the Romans, who

writes that, in the end, Titus—head over heels in love—only moved against the

rebels when he had no choice. And he remained in Berenice’s thrall for all of

his years. Eventually, once his father became emperor, Titus returned to Rome

and Berenice followed, living with him until Titus was finally forced to send

her home and instead to marry a Roman woman who could give him a Roman heir.

And that is the story of Queen

Berenice. Unknown to most today, and yet a woman who invented and re-invented

herself time and time again, eventually positioning herself to attempt to

defuse a full-scale rebellion against Rome by appealing first to the rebels and

then, when that failed, to their future opponent. Queen Esther was successful

where Queen Berenice failed. Is that why we remember Esther, but have totally

forgotten Berenice? Perhaps we should remember her too: a brave, wily, and

daring Jewish woman who did her best to head off catastrophe for the Jewish

people and who, even if she failed, deserves to be remembered as someone who,

at the very least, tried to do good.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.