When we lived in Heidelberg, we often heard it said that the

reason the town was largely spared during the Allied bombing raids that

hastened the end of the Second World War was because General Eisenhower had

already decided to set up the headquarters of the American Army in Europe in

that town and wished it to be, at least more or less, in functioning order

(i.e., with clean running water and an intact electrical grid) when the Germans

finally surrendered. That much apparently is true—but the part of that same

story I’m less sure about is the assertion that Eisenhower chose to spare

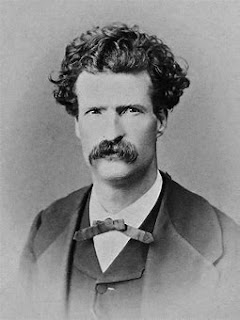

Heidelberg specifically because he fondly remembered reading Mark Twain’s very

funny account of his visit there in his 1880 book, A Tramp Abroad, and thought it would be a kind

of after-the-fact homage to Twain to set up American headquarters in one of the

few German cities with deep roots in American literary history. After all, it had to be somewhere!

A

Tramp Abroad is mostly forgotten today, although it really is very

amusing and interesting, as is its companion work, The Innocents Abroad, which wraps up with Twain’s

extended account of his trip to Israel—then Turkish Palestine—in 1867. I read

both books years ago—I went through a period during which I could hardly read

enough of Mark Twain—and enjoyed them both, as I also did Twain’s other travel

books, particularly Roughing

It (which is

about Twain’s travels in the Old West and Hawaii in the 1860’s) and Life on the Mississippi (about the years he spent as a

riverboat captain on the St. Louis to New Orleans route). For readers who only

know Mark Twain through his fiction, I recommend all these books for the

glimpse they offer into the man himself when he wasn’t writing about Tom, Huck,

and all the rest.

I was brought back to thinking about The Innocents Abroad this summer by an essay by Meir

Soloveitchik in which the author compares Twain’s account of his visit with one

that took place a cool seven centuries earlier, the one undertaken by one of

the greatest of all medieval Jewish scholars and authors, Ramban (i.e., Rabbi

Moshe ben Naḥman, also called

Naḥmanides) in 1267. (To read Soloveitchik’s essay, published in Commentary just last month, click here.)

The thrust of the essay is to show how two authors, both

clearly men of integrity and insight, were able to look out at the same

landscape and see two entirely different things.

For Twain, what mattered most was the dreariness of the

place. He has some caustic comments about the “big” tourist sites—he is

particularly biting about his visit to the alleged grave of Adam within the

confines of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem—but his most

acidulous disdain he pours out on the land itself, which he found barren,

lifeless, and—to say the very least—desolate. It is not at all a flattering

portrait. Nor would or even could anyone reading it cold (i.e., without any

previous sense of attachment to the land) come away possessed of any sort of

interest in ever visiting it personally.

To this uninviting travelogue, Soloveitchik compares Ramban’s

account of his visit. What brought him to Jerusalem is a sad story in its own

right. Ramban apparently acquitted himself quite well in the famous 1263 public

debate about the legitimacy and reasonableness of Jewish beliefs known to

history as Disputation of Barcelona. (For interested readers, a remarkable

graphic novel about the Barcelona Disputation by Nina Caputo and Liz Clarke

called Debating Truth: The Barcelona

Disputation of 1263, was published by Oxford University Press in 2016 and is

extremely readable and at least as interesting as it is upsetting.) By all

accounts he was eloquent and convincing, for which effort he was rewarded by

being charged with blasphemy and eventually exiled from Spain. And so, after

several years of sojourning in various overseas locations, he arrived in Eretz

Yisrael in 1267, precisely six centuries before Mark Twain.

Ramban also found the place desolate and mostly forsaken.

But instead of describing the land as bleak and abandoned, he saw in it a land

in mourning for its former glories. Indeed, he suggested that, just as people tend

only to find true solace in the wake of tragic loss in the company of caring

family members, so does the Land itself exist in a state of misery as it awaits

the return of its children. And so he set to work, playing a major role in

galvanizing the Jews present in the land and, among other things, founding the

famous Ramban Synagogue that has existed ever since in the Old City of

Jerusalem other than during the dark days of the Jordanian occupation from 1948

through 1967. And he also invented Zionism, writing passionate, interesting letters

back to Spain in an attempt to re-awaken a desire among his people to return to

Zion and re-establish Jewish life in the Holy Land.

Soloveitchik’s essay, which I liked very much, set Twain and

Ramban in opposition. But I would like to add a third voice, one almost always

ignored even by Americans otherwise familiar with his work: I am thinking of

Herman Melville, author of Moby-Dick and one of

my personal literary heroes. Melville, the bicentenary of whose 1819 birth

lovers of American books everywhere are celebrating this year, also made a trip to the Holy Land and wrote about it. But he did

so in an entirely different way than Twain.

Melville left behind a complex legacy. Moby-Dick is acknowledged by all as an

American classic, but others of his books, including some truly famous in their

own day, are hardly remembered by anyone. But least recalled of all is surely

Melville’s epic poem, Clarel:

A Poem and Pilgrimage in the Holy Land.

Coming in at a cool 18,000 lines, Clarel is a big read. Avery big read. (My edition is 893 pages long.) Nor is it an easy

one: the plot is extremely confusing, the cast of characters is immense, the

language is obscure in many places, and the style is—to say the very

least--challenging. This is not a book for the faint-hearted.

And yet it has a place in my heart. Twain was writing to be

funny and he succeeded admirably, albeit at the expense of his subject.

Melville was attempting to say something profound and inspiring about the place

he felt the Land of Israel—and particularly Jerusalem—should play in the

American sense of the world and the place of our nation in it. Basing himself

on his own experiences traveling there in 1856, he presents himself (played in Clarel by the character Rolfe) and

Nathaniel Hawthorne (played in Clarel

by Vine) as

close friends seeking spiritual fulfillment on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, then

moves on from there to involve them in the lives of a dizzying amount of fellow

travelers. It’s an interesting premise

and the book could have been a big seller, but that didn’t happen: the initial press

run was a mere 350 books, of which the printer ended up burning the unsold

copies (which constituted more than half the press run) when the author

couldn’t afford to buy them at cost. In 1925, the literary critic Lewis Mumford

famously found the pages still uncut in the copy owned by New York Public

Library, unambiguous proof that the single copy the Library owned had remained

unread for a full half-century. The reviewers, to the extent there were any,

were unkind.

Melville, like Ramban and Mark Twain, found Israel to be, to

say the least, uninviting. In his journal he wrote this: “Judea is one

accumulation of stone: stony torrents & stony roads; stony walls & stony

fields, stony houses & stony tombs; stony eyes & stony hearts. Before

you and behind you are stones.” Nor does he harbor much hope for a Jewish

future in that place, noting that it would be a true miracle if Jewish people were

ever to find it in themselves to create a viable agrarian society in such a

barren, desolate place.

Nonetheless, Melville found in Israel a place of natural

haven for Jews of all sorts. In the endless pages of Clarel, he

describes Jews from India, American converts to Judaism who have chosen to

settle in the Holy Land, Jewish scientists hard at work deciphering the land’s

geological legacy, religious and secular Jewish types, doubters and believers,

socialists and capitalists, farmers (or rather, would-be farmers) and urban

types. In other words, Clarel looks out at the landscape of mid-nineteenth

century Turkish Palestine and sees something remarkably like the State of

Israel today: a Jewish country filled with every conceivable kind of Jewish

soul attempting to make the desert bloom, to create a viable economy, to find

accommodations that make it possible for people of all kinds of beliefs to live

in harmony with each other. Mostly, Melville writes endearingly about Judaism

itself, seeing in the Jewish faith the platform on which the rest of Jewish

life should and does stand. Had the word existed in his day, Melville would

surely have been acclaimed as the most prominent non-Jewish Zionist the world

had ever seen. (For an excellent introduction to Clarel published by

P.J. Grisar in the Forward this summer, click here.)

For all sorts of reasons, American Jews are feeling insecure

these days. The attacks on the synagogues in Pittsburgh and Poway are always in

the background. The sudden, unexpected shakiness of the traditional

bedrock-solid support for Israel in the Congress is (or should be) a source of

intense anxiety. (I personally think that the center will hold, but I share the

sense of foreboding felt at least slightly, I suspect, by all.) The rise of

anti-Semitic incidents both in centers of Jewish life and in places far from

those centers is beyond troubling. And then—at least for me personally—there’s

Melville waiting in the wings with his gigantic poem describing the deep

interpenetration of the American and Jewish dreams, and promoting the idea of the

Jewish attachment to the Land of Israel functioning for Americans as a symbol

of what can be wrought by wholly dissimilar people when they embrace a single

powerful idea.

Melville died in obscurity, his death barely noted and his

name misspelled in the obituary that did appear in the New York Times. It

took decades for Moby-Dick to take its rightful place among the great

American books. And even today many of his works, including some of my

favorites, are read by almost no one at all. But beyond all the rest stands one

immense poem about America and Americans, about the Holy Land and Jews, about

the specific way the future and the past meet in Jerusalem for all who journey

there to seek out its peace.

On the two hundredth anniversary of Melville’s birth, I

invite you all, at least a little, to sample Clarel and to marvel at

what one man, toiling away on East 26th Street, could see of the

future.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.